“3 Questions For” is an ongoing series of quick sketch interviews with notable presenters at MDC events.

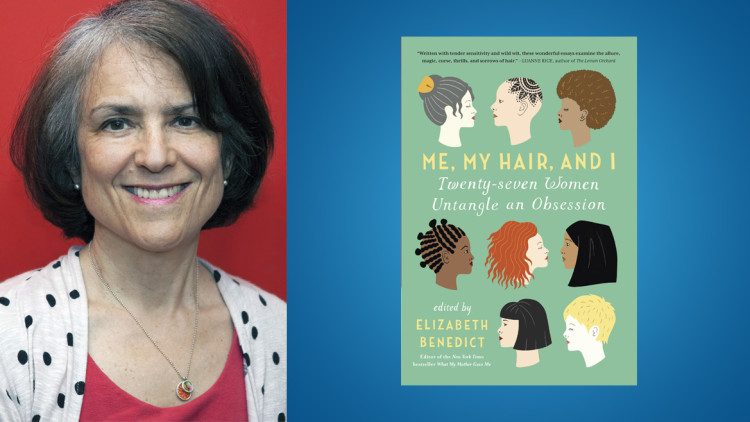

Elizabeth Benedict is the author of five novels, including the bestseller Almost and the National Book Award finalist Slow Dancing. She is the editor of the anthologies “What My Mother Gave Me,” a New York Times bestseller, and “Mentors, Muses & Monsters,” and has written for a number of major publications. Elizabeth will be appearing at the Miami Book Fair in Hair: A Cultural Exploration on Saturday, November 21 from 12:00 p.m. to 1:00 p.m.

Gabriel Riera: Why hair — what is it about this subject matter that made you want to delve into it?

Elizabeth Benedict: Hair is a library of information that talks about who we are, what we want, how we see ourselves and how we want other people to see us. It also seems to be a way, particularly for women, to talk about some very deep issues such as self-worth, mortality, sexuality, and family relations. The topic of hair also speaks to religion, culture, history — it goes very deep because hair is involved in a lot of rituals. It’s a way of presenting oneself but also a way of controlling others. Hair conveys all kind of messages and it seemed like a really rich, complex way of talking about a lot things that are important.

GR: How did you go about putting this book of essays together?

EB: This is the third anthology that I’ve edited and in each of them I’ve asked people to write about specific subjects. Deborah Feldman had been in the Satmar Hassidic sect and has written two books about her life. She writes about having to shave her head the day before she got married, having her head covered for the duration of her marriage and finally coming into her independence when she took off her head scarf.

Marita Golden, an African American woman, has been politically active for decades and wrote an amazing essay called “My Black Hair.” I went to Anne Lamott because I knew she had an interesting hair story — she has dreadlocks and she’s white. I also reached out to Bharati Mukherjee who grew up in India, and Rue Freeman who grew up in Sri Lanka, because I was interested in how other cultures raise daughters around the subject of hair. They wrote these fantastic essays about what hair meant to them growing up and what it means to them as mothers and daughters.

GR: Did you find a common thread in all these stories — was anything surprising in what you read?

EB: There were a lot common threads. I suppose the most salient one was how much hair matters to people. It matters in all kinds of ways. It matters in terms of how people think of themselves sexually, which means it matters in your marriage, in relationships. One of the things that was very surprising was the kind of conflict that hair brings up between mothers and daughters. Deborah Tannen’s essay “When Mothers and Daughters Tangle Over Hair,” touches on how much daughters want to please their mothers and how mothers often say things that sound critical and hurtful even as they are trying to be helpful to their daughters. In these family dynamics, hair becomes a battleground for self-worth, control and power. The intensity, complexity and universality of these conflicts surprised me.

A writer named Patricia Volk wrote a piece called “Frizzball” about all the hair products under her sink and how much each of them cost; how much energy, time and money she spent getting her hair straight. It’s very funny but also very sort of, obsessive. I was familiar with these issues but not all the products. I was surprised at how many there were.

There’s a much wider range of issues involved than just the fashion and beauty thing.

We strike a lot of different notes here. One of the most interesting essays in the book is by Farika Youad, a young woman, who got cancer very young, lost her hair to chemotherapy and ended up with hair tattoos. That’s one end of the spectrum. Another end is the piece by Alex Kuzcynski, who wrote an essay called “And Be Sure to Tell Your Mother,” about women and pubic hair. These essays show that there are all kinds of ways of thinking about the different kinds of hair on our bodies and what it means to us. There’s a much wider range of issues involved than just the fashion and beauty thing.

Another commonality I found is that we all have a relationship with our hair. Like all relationships, it changes. Sometimes you’re getting along really well, and sometimes you’re at odds and you need mediation. It’s a real relationship that changes as your hair and your needs change.